![]()

A strategic inflection point is that moment when some combination of technological innovation, market evolution, and customer perception requires the company to make a radical shift or die.

—Andy Grove, Only the Paranoid Survive

Enterprise

The Enterprise represents the business entity to which each SAFe portfolio belongs.A SAFe portfolio contains one or more Development Value Streams, each dedicated to building, deploying, and supporting a set of Solutions the enterprise needs to accomplish its business mission. In the small-to-midsize enterprise, one SAFe Portfolio can typically govern the entire solution set. In larger enterprises—usually those with more than 500 to 1,000 practitioners—there can be multiple SAFe portfolios, often one for each line of business, or as otherwise structured around the business organization and operating model.

In either case, the portfolio is not the entire business, which is concerned with more than just solution development. Therefore, the enterprise and portfolio stakeholders must ensure that each portfolio solution set evolves to meet the broader business needs. This capability is critical to Business Agility.

Details

SAFe’s primary focus is helping the people who build the world’s most important systems do so faster and better. However, these new solution investments are driven directly by the enterprise strategy. Defining that strategy, deciding how much to invest in the solutions, and driving successful execution is critical for every business. This article describes the necessary collaborations and interactions between enterprise stakeholders and the portfolios for formulating strategy, determining budget allocations, and implementing important enterprise initiatives.

SAFe Portfolios within the Enterprise

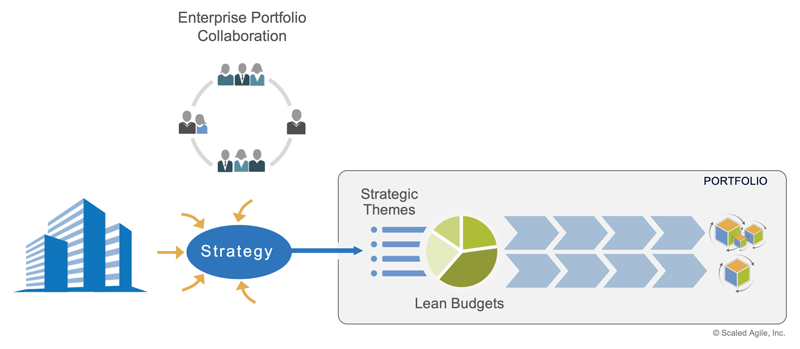

Smaller enterprises and government agencies may only have a single SAFe portfolio, which is able to build all the digitally-enabled solutions needed to fulfill their mission. The portfolio is connected to the enterprise strategy by portfolio Strategic Themes and allocated an approved budget. These elements are established via a collaboration between the enterprise and portfolio stakeholders, as Figure 1 illustrates.

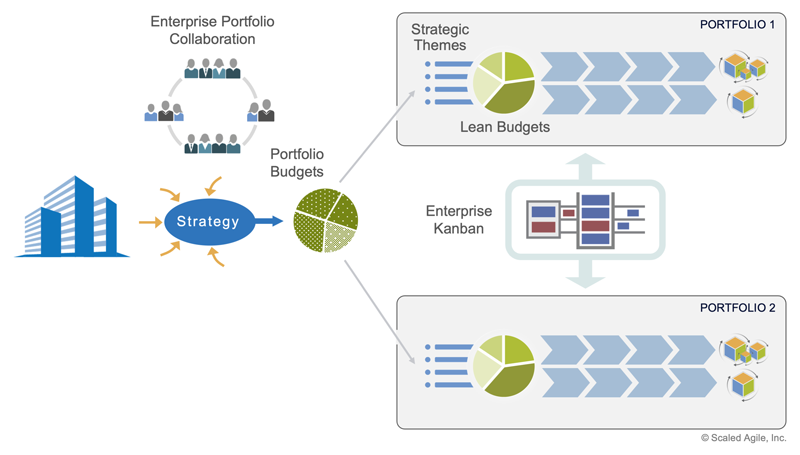

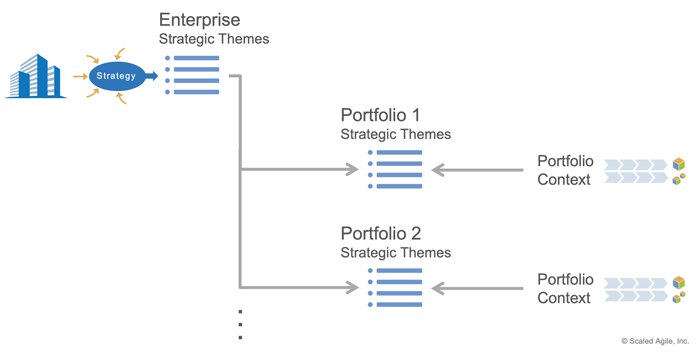

However, many of the world’s largest organizations use SAFe. These enterprises have thousands, and even tens of thousands, of IT, system, application, and solution development practitioners. Not all of these practitioners work on the same solutions or within the same development value streams. It’s more likely that IT and development personnel are organized to support various lines of business, internal departments, customer segments, or specific business capabilities. In this case, each portfolio is connected to the enterprise as previously described, but with three additional considerations, as highlighted in Figure 2.

- Decisions must be made on how best to allocate the total investment in solutions across multiple individual portfolios.

- The enterprise strategy has to be translated into sets of strategic themes, one for each portfolio.

- In addition, there are likely to be enterprise initiatives that will be cross-cutting, i. e. they will affect more than one portfolio. To address this case, many enterprises implement an enterprise Kanban system, which visualizes the flow of ‘enterprise epics’.

Each of the major elements of Figures 1 and 2 are described in the sections below.

Enterprise Strategy Formulation

It all starts with enterprise strategy —a plan of action to achieve the mission of the enterprise. An effective strategy answers four crucial questions about the business:

- What customers and markets do we serve?

- What products and solutions do we provide?

- What unique value and resources do we bring to the endeavor?

- How will we extend these in the future?

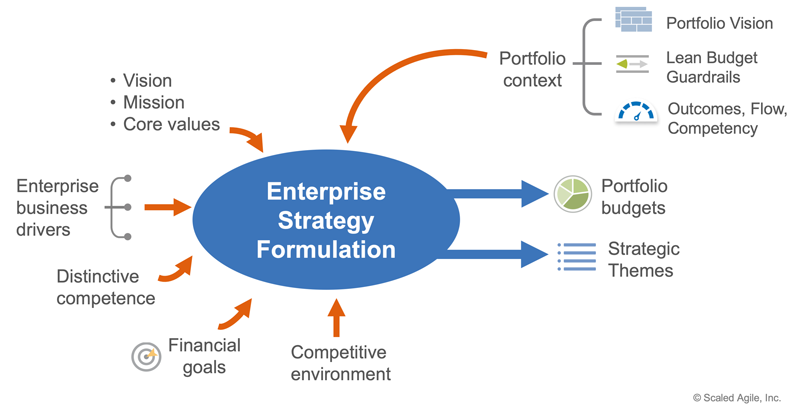

Each enterprise must have an approach to determine its strategy. But most generally, the best way to think about strategy is as a natural output of a logical and reasoned business process. Rather than leaping to conclusions or allowing the loudest or highest-ranking voice to mandate the path, a more effective approach is to collaborate and reason about the strategy inputs. That will generally lead to agreement and alignment about what the strategy should be. One such model was described by Jim Collins in Beyond Entrepreneurship [1]. The adaptation in Figure 3 highlights the inputs to strategy and defines two outputs—portfolio budgets and strategic themes—that the enterprise needs to link strategy to execution.

Each input is discussed briefly below:

- Vision – represents the future state of what the business wants to be. It’s persistent and long-lasting.

- Mission – identifies the current business objectives that implement the enterprise vision and frame the strategy.

- Core values – provide the immutable belief system that governs all individual and corporate behaviors and activities.

- Enterprise business drivers – reflect the emerging industry themes and trends that affect the business.

- Distinctive competence – Strategy naturally leverages distinctive capabilities, the unique advantages that differentiates this business from others, and provides a competitive edge.

- Financial goals – Whether measured in revenue, profitability, market share, or other metrics, financial or other performance goals should be clear to all stakeholders.

- Competitive environment – Competitive analysis identifies the most significant competitive threats to the business.

- Portfolio context – Knowledge of the current state of each portfolio informs enterprise strategy. This is a critical element of enterprise strategy formulation and as such is further elaborated below.

Portfolio Context Informs Enterprise Strategy

Generally, strategic decisions are mostly centralized since they have far-reaching impacts and are often outside the scope, knowledge, and responsibilities of Agile Teams (See Principle #9 – Decentralized Decision-Making). In addition, the business executives and leaders have the ultimate accountability for business outcomes, so they must be ultimately responsible for the strategy.

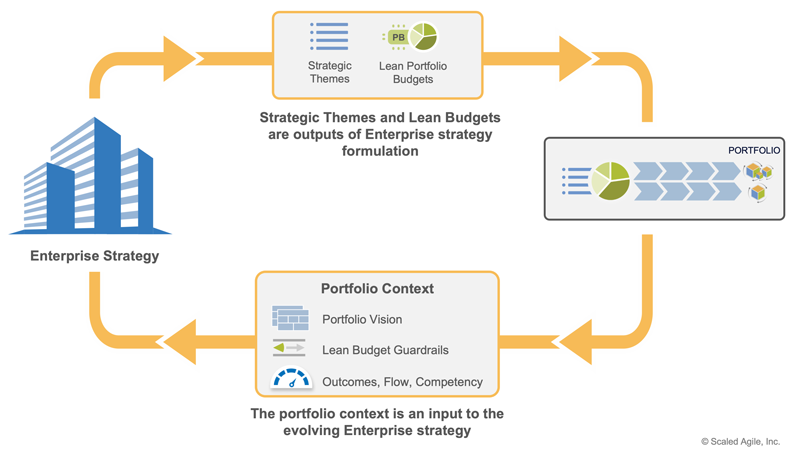

However, many factors that inform potential strategy may not be visible to those enterprise executives. Many of the business challenges, market opportunities, and conditions that exist may be local to various solution offerings. That is why strategy formulation requires continuous collaboration, communication, and alignment with downstream portfolios. In other words, developing an effective strategy demands awareness of the portfolio context. This includes Portfolio Vision, the Lean Budget Guardrails that govern the portfolio investments, and Metrics that measure business outcomes, flow, and organizational competence, and as illustrated in Figure 4.

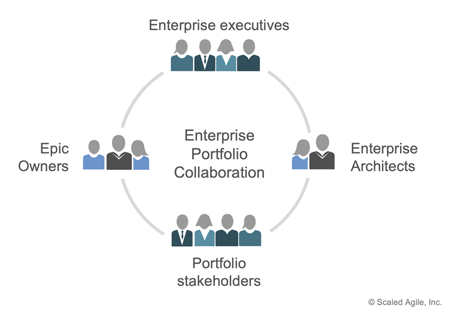

Enterprise Portfolio Collaboration

Collaboration between the enterprise and portfolio stakeholders is critical to achieving business goals. While typically led by the most senior enterprise business and technology stakeholders, the process includes participation from portfolio stakeholders who bring important context from their respective value streams, as Figure 5 illustrates.

Participants in this critical collaboration include:

- Enterprise executives who have the ultimate responsibility for business outcomes

- Some portfolio stakeholders often have a significant role in both the portfolio vision and enterprise strategy. These can include Business Owners who have primary business and technical responsibility for ROI, system and solution architects, and members of the APMO who support successful execution and operational excellence.

- Epic Owners play a key role in moving large initiatives through and across portfolios

- Enterprise Architects help assure that strategies are anchored in feasible technological innovations. In addition, awareness of new innovations often provides new strategic opportunities

Connecting Enterprise Strategy to the Portfolio with Strategic Themes

The formulation of strategy is one of the most complex and critical enterprise endeavors. It isn’t necessarily feasible or even desirable to formally ‘document’ strategy in a highly structured way (though the Appendix below shows a good starting approach). Nor is it exactly obvious as to who needs to communicate strategy, to whom, and when.

To address this, SAFe recommends using strategic themes as a summary artifact to communicate strategic intent. In a situation where an enterprise has a single portfolio, a single set of portfolio strategic themes provide the needed connection to the enterprise strategy.

In a multi-portfolio organization, an additional set of central ‘enterprise strategic themes’ may be needed to inform and connect the strategy of the individual portfolios as is illustrated in Figure 6.

A typical format is to simply use a short phrase (e.g., ‘Expand to the European market’, ‘Transition to the cloud’, ‘Enable consumer self-service’). A more rigorous approach is to express strategic themes as OKRs (Objectives and Key Results) where a concise objective is supplemented with key results – specific, measurable achievements, which, in turn, are measured via KPIs. Either way, strategic themes communicate strategic intent to everyone in the organization.

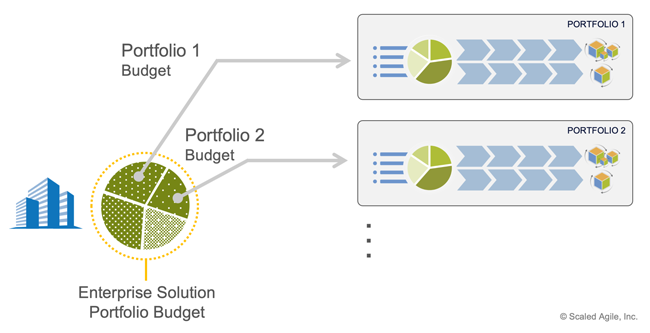

Allocating Portfolio Budgets

An effective lean enterprise adaptively and dynamically allocates funds across portfolios to execute evolving strategy. To support this flexibility and speed of decision-making, rather than funding individual projects, SAFe enterprises instead allocate budgets to each portfolio, which is then empowered to make the investments that maximize value returned.

As described in the Lean Budgets article, each portfolio then allocates budgets to the development value streams within that portfolio.

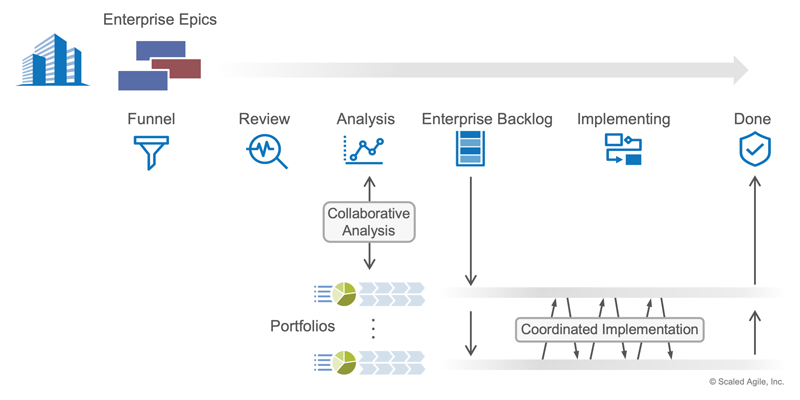

Managing Cross-Portfolio Initiatives

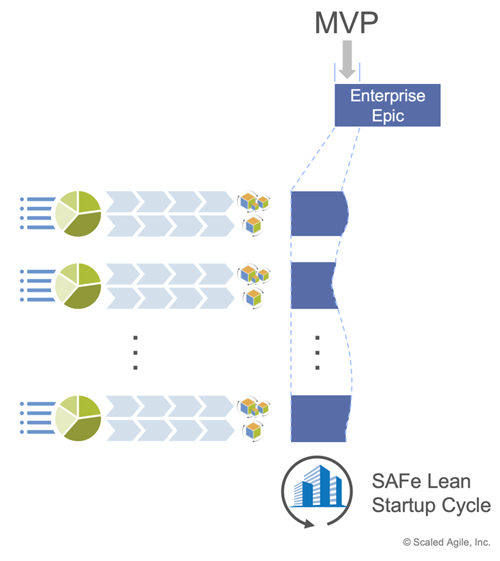

In a SAFe enterprise, every solution is managed within a specific portfolio. Some initiatives, however, cut across a broad solution landscape and require the collaboration of multiple portfolios (for example, ‘implement GDPR compliance across all enterprise solutions’). Many of these are quite critical and often not subject to debate (like the GDPR example). And yet, if not managed appropriately, initiatives that come from this highest organizational level—whether they carry significant strategic importance or not—can still be ‘pushed’ onto portfolios and thus overload the system.

To address this, enterprise epics are established to define and reason about this important work. And in a manner similar to a Portfolio Kanban, the work intake process at this level helps the organization match demand to capacity, prevent overload, and foster fast delivery of enterprise value.

The process can be summarized as follows:

- All big new cross-portfolio initiatives enter the Funnel and are progressively elaborated through Review and Analysis in close interaction with the portfolios that will do the work.

- In a manner analogous to portfolio epics, the epic hypothesis statement and the lean business case can be used to define and further elaborate enterprise epics.

- A “Go” or “No-Go” decision is made once the analysis is complete.

- Portfolios then pull approved enterprise epics into implementation and create portfolio epics to describe the portion of the work they are committed to.

In a manner similar to portfolio epic owners, ‘enterprise epic owners’ foster and drive collaboration around the organization’s cross-portfolio initiatives.

In some cases, both the scope and the implementation rhythm of the corresponding portfolio epics may need to be synchronized across the portfolios. For example, even if the portfolios do not have substantial interdependencies, an enterprise epic may require a coordinated MVP (Minimal Viable Product)—a thin slice of effort across the organization— to validate or disprove the underlying business hypothesis (Figure 9). The MVP limits the risk of investment and provides for exploratory discovery of even the largest and most critical enterprise initiatives (see the SAFe Lean Startup Cycle in Epics).

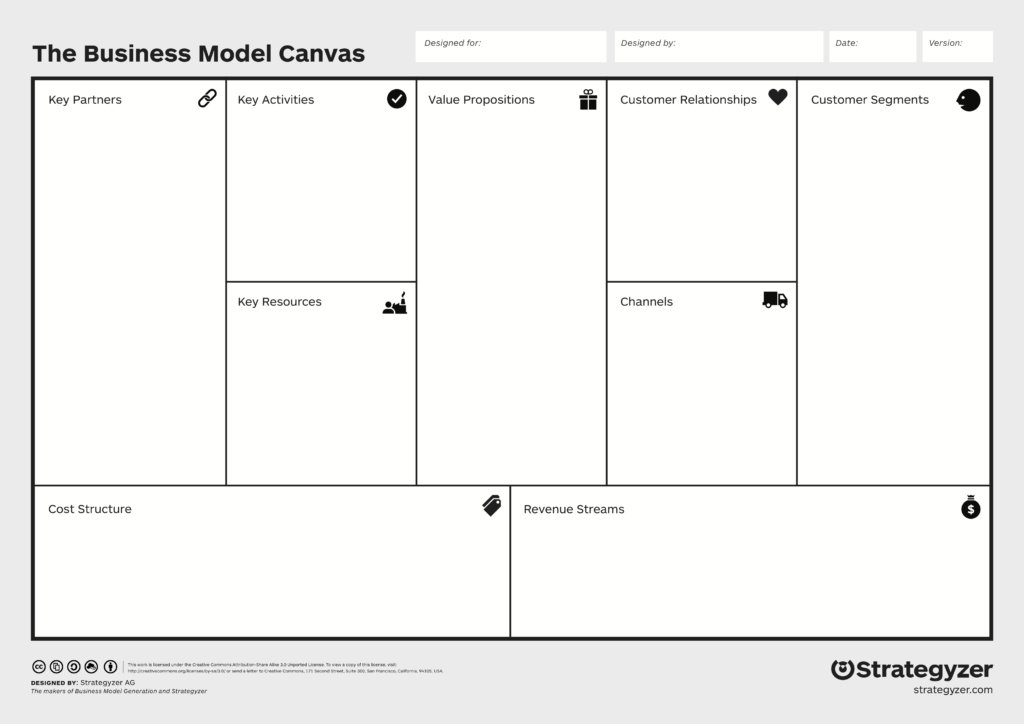

Appendix: Capturing Strategy in a Business Model Canvas

The concepts outlined in this article provide a logical and reasoned process in which enterprise strategy formulation reflects internal and external objectives, business conditions, and the organization’s larger purpose. Moreover, once decided, the plan must be communicated and made clear to all stakeholders. There is, of course no ‘one right way’ to do this. One popular way to frame a strategic plan is through the Business Model Canvas (BMC) [2]. The BMC is a one-page template that summarizes the most important aspects of a business model, as illustrated in Figure 10.

Download The Business Model Canvas

The BMC can be used to model any business, from startup to global enterprise. The BMC comprises nine somewhat independent building blocks that help clarify thinking and focus when describing a business model. The ‘blocks’ of the canvas are as follows:

- Value propositions are the set of products and services the enterprise offers.

- Key partners are the various buyer-supplier relationships and business alliances that facilitate achieving the value proposition.

- Key activities are the most important actions the enterprise takes to deliver its products and services.

- Key resources are the critical human, physical, intellectual, financial, and other capabilities and assets the enterprise has to achieve its objectives.

- Customer relationships reflect the types of relationships needed to effectively apply and leverage the business’ products and services.

- Customer segments define how the business views and treats various sets of customers differently based on their common attributes.

- Channels explain how the enterprise delivers its products and services to intermediaries, customers, and end-users.

- Cost structure highlights the various elements of development, production, deployment, operating, and support costs associated with the business’ products and services.

- Revenue streams reflect how the enterprise receives financial compensation for its products and services.

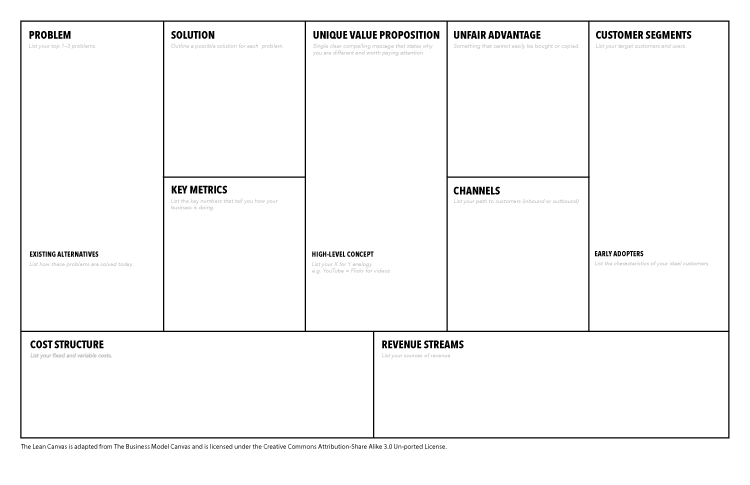

Thinking Like a Lean Startup with the Lean Canvas

A popular variant of the BMC is the Lean Canvas created by Ash Mayura [3], illustrated in Figure 11 [4].

Download The Lean Canvas

The lean canvas was based on the thinking that originated in Lean Startup [4] and is designed to address startup enterprises’ unique opportunities and challenges. It’s now also applied to innovation efforts in larger enterprises. The Lean Canvas is similar to the BMC, but it focuses more keenly on the nature of the problem to be solved, as well as the unique competencies of an enterprise that can be used to address emerging opportunities.

Like the BMC, the Lean Canvas has nine ‘blocks.’ The ‘channels,’ ‘customer segments,’ ‘revenue streams,’ and ‘cost structure’ is shared with the BMC. However, the Lean Canvas replaces the other five blocks with the following:

- Problem describes the problem that exists in the marketplace before designing a potential solution. This is a signature aspect of Design Thinking.

- Solution defines the key characteristics of a proposed solution.

- Unique Value Proposition describes the unique skills, resources, and assets a business brings to the endeavor. In other words, “why you are different and worth getting attention.” [3]

- Unfair advantage describes the tangible and intangible assets of the business that cannot be easily bought, copied, or replicated by competitors who address the same problem.

- Key metrics identify the critical, early measures that indicate whether the new solution is likely to address the identified problem.

The Lean Canvas helps define an actionable business plan. It focuses on customer problems, solutions, key metrics, and competitive advantages. In contrast, the Business Model Canvas is a strategic management tool, allowing you to describe, design, challenge, invent, and pivot your existing business model [5]. While neither canvas captures all the elements of an enterprise strategy, both are useful tools to evolve the organization’s solution portfolios. The choice is up to the enterprise: Use either or both canvases, or develop a derivative best suited to a particular business context.

Learn More

[1] Collins, Jim, and Lazier, William. Beyond Entrepreneurship: Turning Your Business into a Great and Enduring Company. Prentice-Hall, 1992. [2] Osterwalder, Alexander, Yves Pigneur, and Tim Clark. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers. John Wiley & Sons, 2010. [3] Maurya, Ash. Running Lean: Iterate from Plan A to a Plan That Works. O’Reilly Media, 2012. [4] The Lean Canvas. https://leanstack.com/leancanvas [5] Ries, Eric. The Lean Startup: How Today’s Entrepreneurs Use Continuous Innovation to Create Radically Successful Businesses. Random House, Inc, 2011. [5] https://www.eqengineered.com/insights/why-use-lean-vs-business-model-canvas

Last update: 27 September 2021