![]()

“If there’s one thing government needs desperately, it’s the ability to quickly try something, pivot when necessary, and build complex systems by starting with simple systems that work and evolve from there, not the other way around.”

—Jennifer Pahlka, Founder, Code for America, Former U.S. Deputy CTO 2012 [1]

SAFe for Government

SAFe for Government is a set of success patterns that help public sector organizations implement Lean-Agile practices in a government context.The foundations of Lean and Agile thinking have led to higher success rates versus waterfall methods in software and systems development in the private sector. Government programs are starting to experience similar results using these same patterns. However, government agencies must address unique challenges in Lean-Agile transformations. The recommendations and best practices in SAFe for Government provide specific guidance to address these concerns.

(For more information on this topic, including links to pages containing a wealth of additional resources and videos, check out our Agile in US Government page on ScaledAgile.com.)

Details

Why SAFe for Government?

Lean-Agile and DevOps practices are gaining interest among the leaders responsible for the largest most complex systems built for government worldwide. Much of that interest is driven by the internal and external forces changing how government agencies provide services to citizens and operators. Perhaps not surprisingly, these forces are similar to those found in commercial markets:

- The need for business (mission) agility

- Impact of digital transformation

- The rise of social media and instant access to information about IT spending

- Increasing citizen expectations

- Technical debt and antiquated systems driving IT modernization initiatives

- Rapid changes in defense systems and the global cyber threat environment

Like for-profit organizations, the government is increasingly dependent upon technology. Yet, the traditional approaches to developing and sustaining new technologies have proven to be insufficient for creating 21st century-solutions. Agile practices have shown promise. However, the size and complexity of government systems, ranging from an unemployment benefits website for French citizens to the U.S. F-22 fighter jet, require more than team-level Agile practices can provide.

Background of Agile Adoption in the U.S. Federal Government

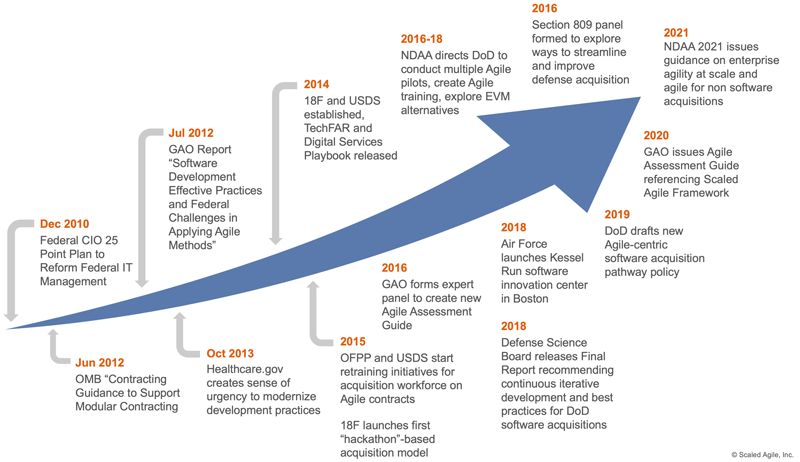

As a case in point, since 2012, interest in Lean-Agile methodologies for government technology development programs has been increasing exponentially in the U.S. In July of that year, the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) issued a report recommending specific practices for Agile development, along with 14 unique challenges to Agile adoption in government. [2] That same year, the U.S. Office of Management and Budget (OMB) directed agencies to change their procurement practices from bloated long-term projects to a more modular contracting approach that aligned with an iterative development model. [3] Although these were positive signs that the decades-old commitment to waterfall processes was relenting, agencies were still slow to adopt a different way of working. Figure 1 shows a timeline of the significant events that have driven Lean-Agile adoption in the U.S. federal government.

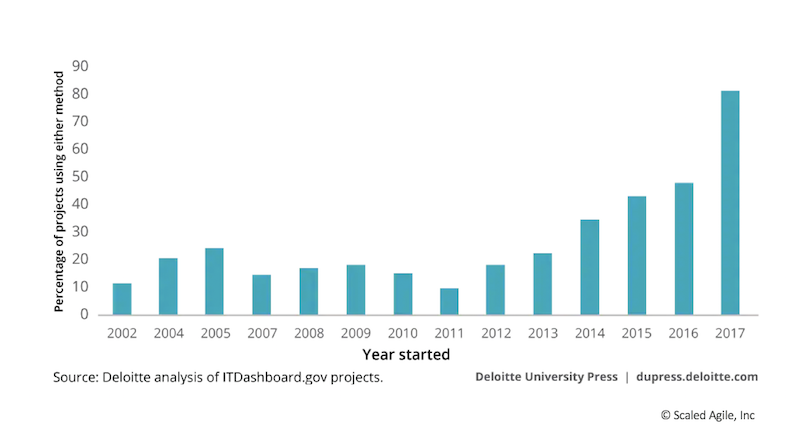

The troubled launch of the U.S. Healthcare.gov website in the latter part of 2013 increased the interest in adopting Agile almost overnight. This site was built to allow citizens to obtain health insurance as part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). For weeks, the website’s initial difficulties were highlighted in the national news, exposing many of the weaknesses in the traditional development practices common to government technology programs. [4] The public focus these events put on government IT programs drove increased openness to adopt more modern development practices. In an analysis of Agile adoption in the U.S. Federal Government published by Deloitte in 2017, [5] the percentage of federal IT projects that report using Agile or iterative processes has grown dramatically since 2012, as shown in Figure 2.

The increased interest in Lean, Agile, and DevOps accelerated when two new U.S. government agencies, 18F and U.S. Digital Service, were created to attract talent from industry to help bring modern, Silicon Valley-like practices to federal IT programs. The Digital Services Playbook and the TechFAR Handbook were two early resources they provided to help leaders in government programs understand how to modernize development practices and adjust the acquisition process to support Agile contracts. The number of additional government-authored resources on Agile adoption has grown significantly, as has the number of published success stories of federal programs getting better results after their transformation to Lean-Agile practices. One agency, the Department of Homeland Security, has made Agile the formal standard for software development. In September 2020 the Government Accounting Office (GAO) released its draft of The GAO Agile Assessment Guide: Best Practices for Agile Adoption and Implementation for government programs using Agile practices. Congress continues to direct increased training in Agile as well as authorizing the modernization of acquisition practices to support Agile through legislation such as the annual National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA).

Agile Adoption in the Global Governments

Similar trends are being experienced in the development of systems for state and local governments, as well as governments in countries across the globe. The UK government has been engaged for several years in an Agile transformation effort that spans hundreds of Agile teams across its many departments and agencies. Pôle emploi (French employment agency), the Dutch Tax Authority, and the Australian Post (postal service) are examples of global government agencies that have used SAFe to guide their transformations to Lean-Agile at scale. In the case of Pôle emploi, their transformation has resulted in better on-time delivery of employment benefits and increased satisfaction in the agency’s services by both hiring businesses and job seekers.

Government as a Lean Enterprise

Increasingly, government agencies are being challenged by the same forces of change that are driving their commercial counterparts to accelerate Lean-Agile transformations. The need for business (mission) agility, digital disruption, globalization, ever-increasing cyber threats, aging legacy systems, and increasing dependency on technology for business and mission success are just a few of the factors that are equally concerning for both government and industry.

The hallmark of a Lean Enterprise is the ability to deliver the best quality and value in the sustainably shortest lead time. SAFe provides guidance by describing the success patterns that help organizations achieve these competencies. The evidence provided by the many case studies of SAFe implementations in government agencies suggests that these competencies are as applicable to public sector organizations as they for commercial enterprises.

How SAFe Enables Lean-Agile and DevOps in Government

“In 10 months’ time, we have turned a failing effort into a success story for the warfighter, for our organizational culture, and for the taxpayer. We could not have executed a turnaround this fast without SAFe …”

— Scott Keenan, JLVC Program Manager, Joint Staff (U.S. Department of Defense)

SAFe Adoption in Government is Growing

Many government technology programs are large and complex, involving hundreds (sometimes thousands) of practitioners. Solutions are built by multiple teams of teams that need to:

- Plan and work together

- Manage cross-team dependencies

- Integrate frequently

- Demonstrate working software and systems iteratively

- Share learning for relentless improvement

Often, these large solutions include small groups of government employees working closely with large numbers of contractor personnel. Multiple suppliers on different contracts may work on the same program across dispersed geographies. High assurance and compliance requirements, burdensome governance regulations, and abnormally long acquisition lead times further complicate government projects.

Most of these challenges are also common in large commercial organizations. Companies in the Global 1000 have used Lean-Agile to build core banking systems, satellites, farming combines, clinical and financial systems for health networks, and much more. For these organizations, SAFe has emerged as the leading framework of practices for Lean-Agile at scale; the positive results have been documented in published case studies. In the last five years, an increasing number of government agencies have also adopted SAFe as the process model for technology development for all the same reasons as their commercial counterparts. Practitioners who have used SAFe in both contexts have reported that there are far more similarities in development between industry and government than there are differences. As shown in Figure 3, SAFe is now being used in hundreds of programs across a large number of government agencies.

The Government has Unique Challenges Along the Path to Lean-Agile Adoption

Even with the increased momentum toward Lean-Agile and using SAFe, several barriers delay widespread adoption. The most frequently cited challenges include:

- Poor implementations of Agile in the past, creating a reluctance to try again

- Waterfall-centric governance and lifecycle policies that are not easily changed

- An acquisition workforce that lacks experience with Agile contracts and Lean contracting practices

- Project orientation, versus continuous-flow-of-value mindset, is deeply engrained in government culture

- Long acquisition lifecycles create tremendous waste and delays in delivering value

- Lack of a common enterprise Lean-Agile framework leads to a limited synergy between programs

Although these problems look similar to those faced by commercial companies, the organizational context, culture, and governance authorities in the public-sector environment are truly unique. Government acquisition processes and laws are intended to create a fair playing field among potential providers, but they can also create bureaucracy and delay unlike anything the private sector experiences. In addition, government agencies do not have the competitive market dynamic and profit motive that drives rapid change and innovation in a commercial environment. Instead, funding is typically provided by legislative bodies in politically-charged annual appropriations processes that move slowly. Even the concept of ‘value’ in a government technology program is often difficult to conceptualize and measure.

The Solution – Government-Specific Guidance for SAFe

Because factors in government technology development are specific to these environments, specialized guidance is required to help change agents as they lead transformations. The links that follow connect to articles that address the most common challenges adopting SAFe in government programs and the best practices that support transitioning to a Lean-Agile model.

Building on a solid foundation of Lean-Agile values, principles, and practices. Waterfall ways of thinking and processes are deeply ingrained in government technology programs. Simply mimicking practices like daily standups and working from backlogs will not achieve agency agility. Government leaders and practitioners alike, along with their industry partners, must understand how and why Lean-Agile is fundamentally different than past approaches to technology development.

Creating high-performing teams of teams of government and contractor personnel. Lean-Agile development is a team sport. Teams on government programs often include a combination of government and contractor personnel. Too often the relationship between these entities is more antagonistic than cooperative. This inhibits the development of high performing teams and ultimately the rapid delivery of valuable quality solutions.

Aligning technology investments with agency strategy. Government technology programs can be proposed, approved and funded for a variety of reasons. Technology investments are often made on the basis of assumed funding of past initiatives without the benefit of a periodic review of holistic portfolios of systems. The best use of limited development funds is achieved by ensuring that priorities are aligned and in harmony with the strategic imperatives of the agency.

Transitioning from projects to a lean flow of epics. The start-stop nature of the ‘project metaphor’ for technology development leads to committing to point solutions too early in the process when there are too many unknowns and committing to delivering all planned features even if completing the highest priority features delivers most of the value. Projects also encourage moving people to the work instead of flowing work to teams through single piece flow backlogs. The Lean alternative is to organize large efforts into Epics and manage them inflow from a prioritized backlog, built by long-lived teams of teams.

Adopting Lean budgeting aligned to development value streams. Along with the shift from projects to a lean flow of Epics, there is a change in how to budget. Instead of funding individual pieces of work, budgets fund “the factory” that can build whatever the agency needs based on priorities. Since priorities can continuously shift and change, this approach avoids the wasted expense and delay of change orders or entirely new solicitations in order to shift investments from one initiative to another, enabling agency agility.

Applying Lean estimating and forecasting in cadence. Lean-Agile practices recognize that traditional estimating and forecasting techniques often fail because there are too many unknowns when building systems that are entirely new. These traditional techniques also create the phenomenon of locking programs into the one right answer that was created up front and used to define contractual terms with multiple vendors. Lean estimating and forecasting techniques are lightweight and provide needed adaptability to constantly changing conditions while still providing critical reporting and accountability.

Modifying acquisition practices to enable Lean-Agile development and operations. Fewer barriers to Lean-Agile adoption in government are as daunting as the legacy acquisition process. Contracting officers depend on tried and true boilerplate language for each of the new acquisitions that are firmly grounded in waterfall terms and conditions. Programs cannot be truly Agile if contractors are required to perform in ways that run counter to Lean-Agile values and principles. Transforming to a new way of development requires new templates for contracting officers that allow vendor partners to also be Lean-Agile.

Building in quality and compliance. The goal of Lean-Agile is to create a continuous and sustainable flow of value in technology solutions. Continuous flow is defeated if our governance processes such as verification and validation remain big batch activities performed only at the end of a project. Changing the way the development team works is only part of the answer. Every part of the technology value stream including operations and governance must also work in flow and in smaller batches. This builds quality and compliance into the solution versus inspecting it in as part of one big batch before release.

Adapting governance practices to support agility and lean flow of value. Traditional governance standards for technology development are also deeply rooted in a waterfall model. They require programs to plan everything up front, commit to and budget for one right solution before the work begins, provide detailed project plans for unknown work, pass through arbitrary stage gates, and much more. Lean-Agile methods serve the original intent—to provide sufficient oversight to ensure the delivery of mission-enabling capabilities within a reasonable time and cost—but through the use of alternative processes and artifacts that support a continuous flow of value.

NOTE: These recommendations for Lean-Agile adoption in government do not require a different version of SAFe or suggest modifying SAFe terms and practices to fit government protocols. In fact, experienced practitioners in government services have reported that they achieve the best results when the SAFe model and terminology are used without modification. Using the terminology that is native to SAFe allows program personnel to take advantage of the classes, articles, books, forums, and other information sources necessary to successfully implement SAFe practices. The articles behind each of the practices above explain the specific patterns used by government programs to overcome the most common concerns when transitioning a federal IT initiative to SAFe.

Summary

Government adoption of Lean-Agile has accelerated to the point where most programs (80%+ in the U.S. according to a Deloitte study) are using some form of Agile or iterative development. However, Agile practices are often limited to development teams and do not address the program and portfolio challenges of strategy alignment, budgeting, project-centric planning, acquisitions, governance, compliance, and more. Agencies also lack a common language and set of enterprise-wide practices to create synergies between programs and practitioners. With this SAFe for Government guidance, supported by the corresponding SAFe for Government course, agency leaders will have the tools to overcome common barriers to SAFe adoption and Lean-Agile practices, enabling better results.

Learn More

[1] Pahlka, Jennifer. Coding a Better Government. http://bit.ly/2GwFhO1 [2] Software Development: Effective Practices and Federal Challenges in Applying Agile Methods. General Accounting Office (GAO), July 2012. https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-12-681 [3] Contracting Guidance to Support Modular IT Development. Office of Management and Budget (OMB), June 2012. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/blog/2012/06/14/greater-accountability-and-faster-delivery-through-modular-contracting [4] Brill, Steven. Code Red: Inside the nightmare launch of Healthcare.gov and the team that figured out how to fix it. Time, March 10, 2014. http://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,2166770-2,00.html [5] Viechnicki, Peter, and Mahesh Keikar. Agile by the Numbers: A data analysis of Agile development in the US federal government. May 5, 2017. https://www2.deloitte.com/insights/us/en/industry/public-sector/agile-in-government-by-the-numbers.html [6] Pawlinkowski, Ellen. USAF’s Pawlikowski: DoD Use of Agile Software Development ‘Critical’. https://youtu.be/nQUpplJVjqI [7] The Digital Services Playbook. US Digital Service. https://playbook.cio.gov/ [8] The TechFAR. US Digital Service. https://techfarhub.cio.gov/handbook/ [9] The TechFAR Hub. US Digital Service. https://techfarhub.cio.gov/ [10] Modular Contracting. 18F. https://modularcontracting.18f.gov/ [11] Digital IT Acquisition Professional Training. Federal Acquisition Institute. https://www.fai.gov/media_library/items/show/27 [12] Agile Acquisitions 101. Federal Acquisition Institute. https://www.fai.gov/media_library/items/show/81 [13] Eggers, William D. Delivering on Digital: The Innovators and Technologies that are Transforming Government. Deloitte University Press, New York, 2016. [14] The GAO Agile Assessment Guide: Best Practices for Agile Adoption and Implementation. https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-20-590G

Last update: 10 February 2021